In response to COVID-19 and the nationwide school closures that followed, the federal government passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Through these policies, the USDA was able to grant meal waivers to help schools and community organizations provide meals and snacks during COVID-related school closures (Aussenberg & Billings, 2020; Barton, 2020). Through the Seamless Summer Option (SSO) and the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP), these waivers increase flexibilities for where, when and how meals are served during COVID-19 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020). These waivers include the following:

- An SSO/SFSP Area Eligibility Waiver that allows the summer meal program to serve areas where less than half of the children are from low-income households;

- A Meal Time Waiver that allows for meals to be served outside standard meal times;

- A Non-congregate Feeding Waiver that allows meals to be provided outside of typical group settings; and

- A Nationwide Parent/Guardian Meal Pickup Waiver allowing parents and/or guardians to pick up meals for their children without the student being present.

In response to these policy changes and the important role that schools and other meal service sites have played during the pandemic, the Social Policy Institute set out to explore physical proximity to meal access points before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in St. Louis, Missouri. As many low-income students lack adequate transportation and most alternative access plans require meals to be picked up at these locations (see McLoughlin et al., 2020), physical proximity to meal access points can be an important factor for students’ health and well-being during the pandemic.

We employ a gravity-based accessibility method known as a Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (2SFCA) (Radke & Mu, 2000). This approach effectively takes into account the number of low-income families in a defined geographic region (demand) and the number a meal access points within that region (supply). In doing so, we can understand accessibility in a manner that accounts for both supply and demand of meals.

How did school meal accessibility and participation change during COVID-19?

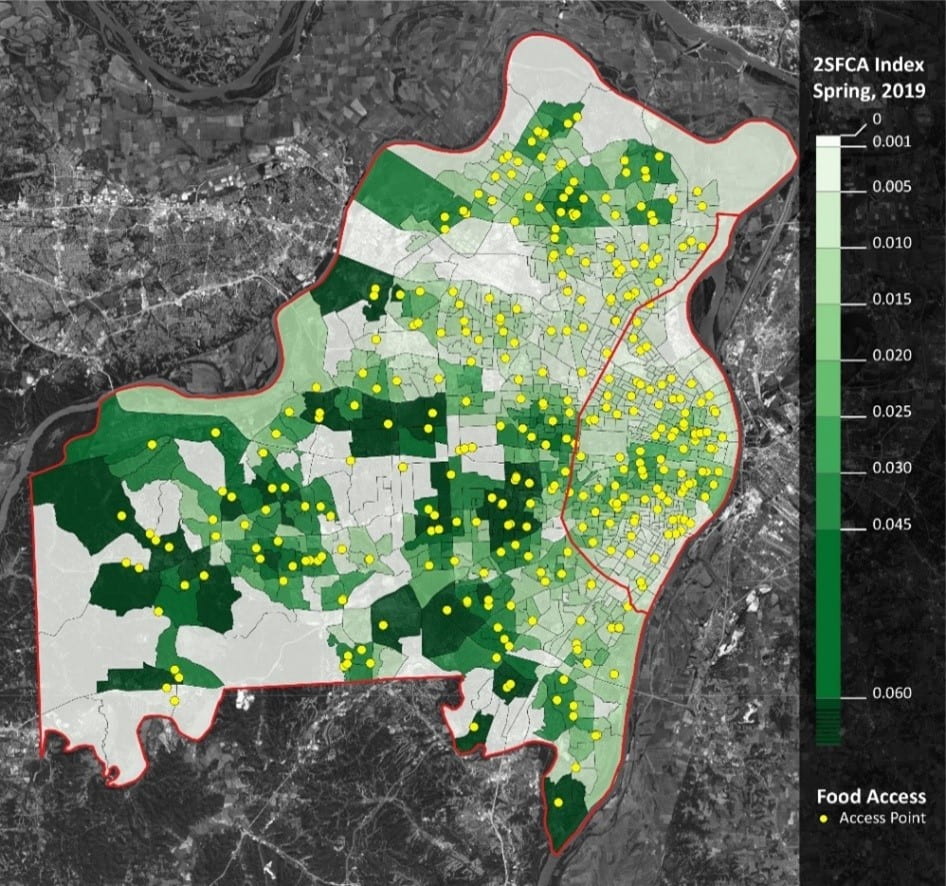

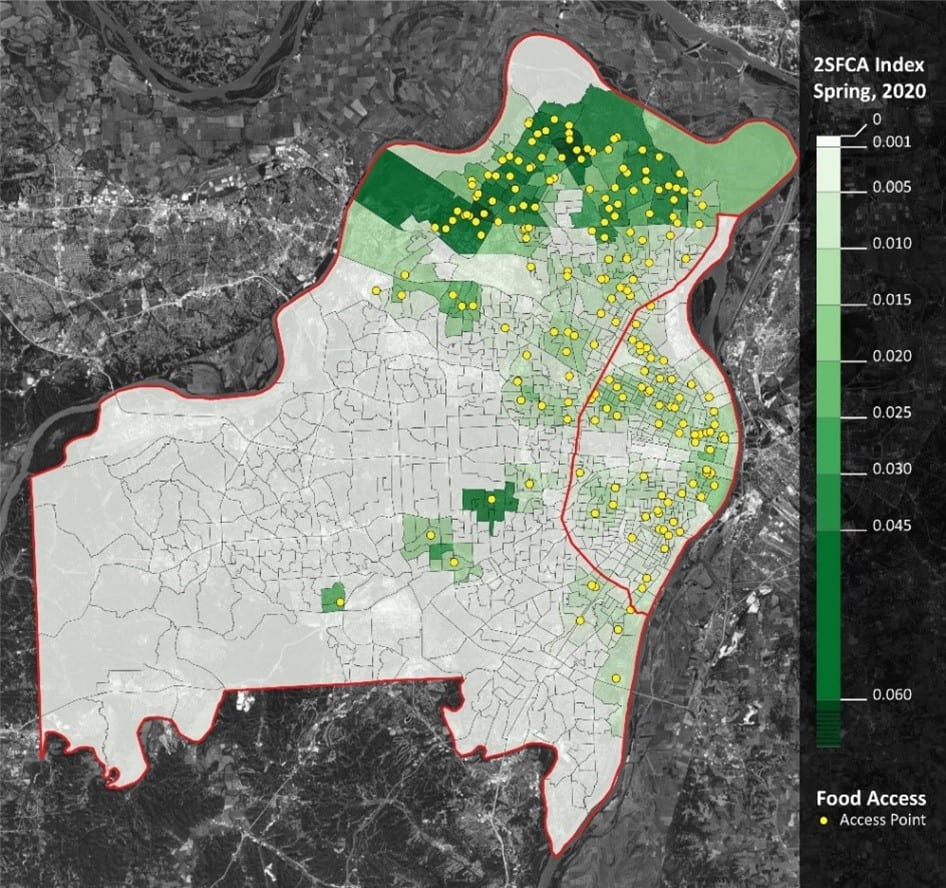

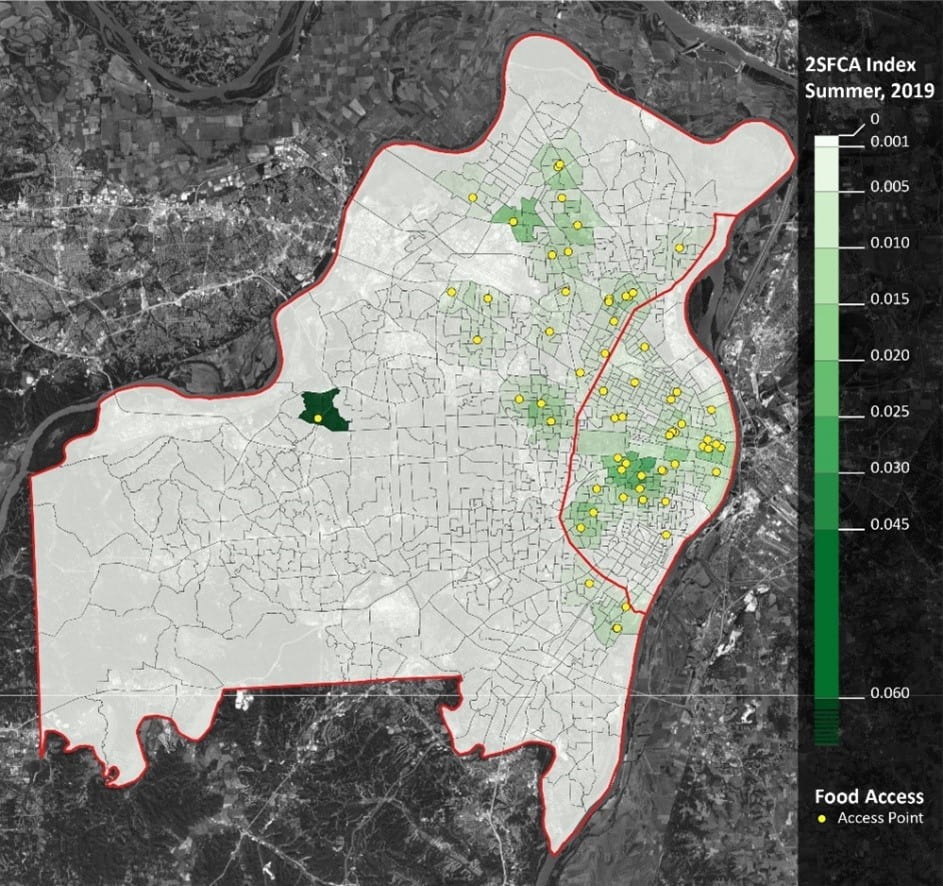

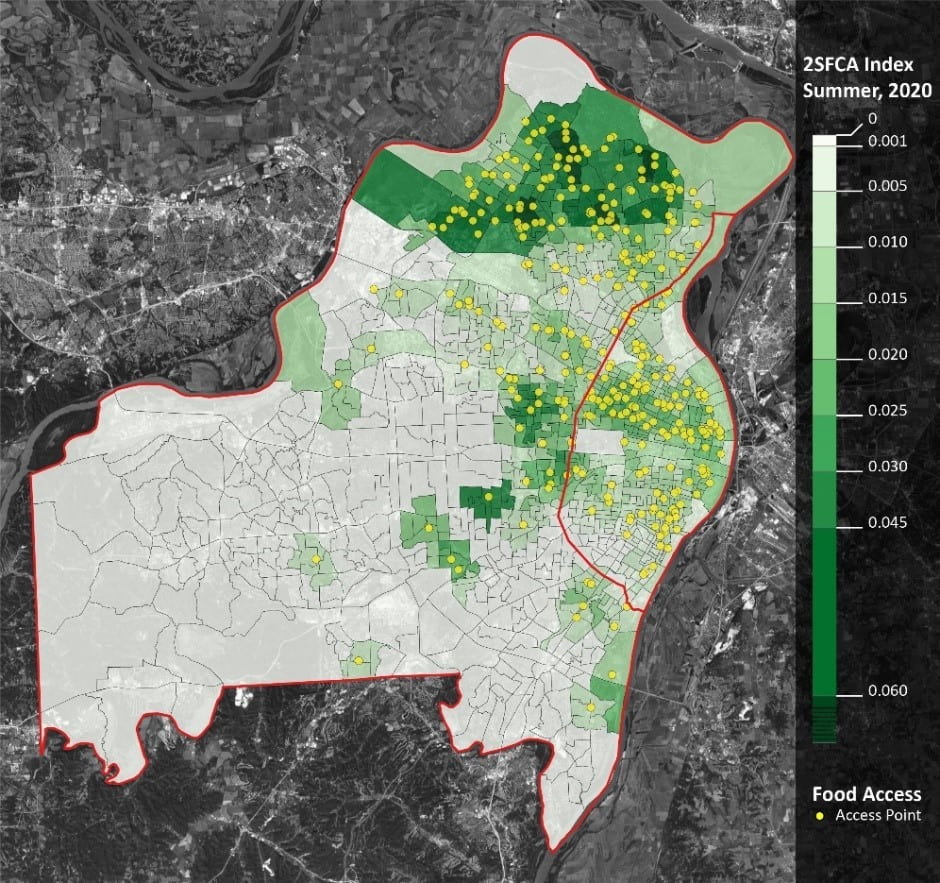

When comparing spring 2019 (Figure 1) to spring 2020 (Figure 2), meal accessibility decreased overall during COVID-19, yet increased slightly in the northern region of St. Louis County. However, when comparing summer 2019 (Figure 3) to summer 2020 (Figure 4), meal accessibility increased overall during COVID-19—especially in the urban core of St. Louis City, the northern region of St. Louis County, and the region near the western boundary of St. Louis City.

Figures 1. Meal Accessibility (Spring 2019)

Notes: St. Louis City is the area east of the red line. St. Louis County is the area west of the red line. Dots represent meal access points. Darker shades represent greater accessibility.

Figures 2. Meal Accessibility (Spring 2020)

Figure 3. Meal Accessibility (Summer 2019)

Figure 4. Meal Accessibility (Summer 2020)

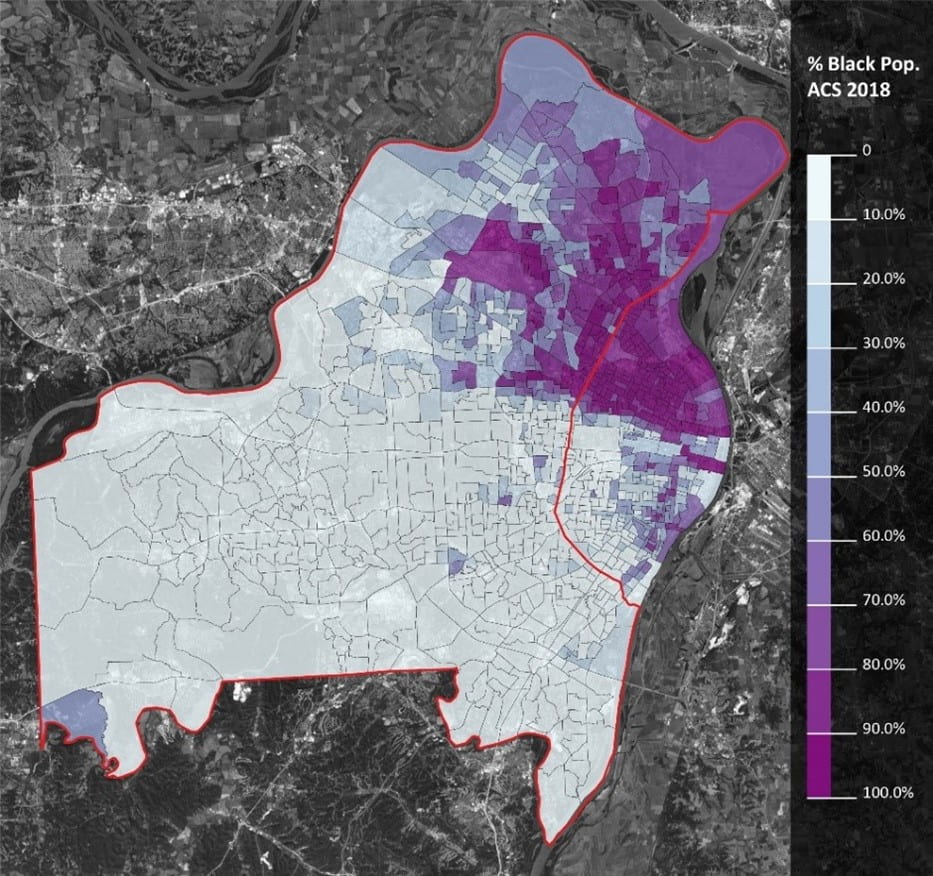

When considering measures of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, the COVID-19 policies and practices appear to have had a positive impact on Black and low-income students during the summer. Here, the expansion of meal access points relative to need during summer 2020 tended to occur in areas with higher proportions of Black (Figure 5) and low-income families (Figure 6). However, with the exception of the northern region of St. Louis County, the expansion of meal access for Black and low-income families was largely not replicated in the Spring of 2020.

Figure 5. Percent Black Population

Note: Darker shades represent greater proportions of Black individuals.

Figure 6. Low-Income Population

Note: Darker shades represent greater proportions of individuals living in poverty.

COVID-19 Policies Could Reduce Child Food Insecurity Long-Term

The expansions and policy innovations around school and summer meal programs due to COVID-19 provided some of the infrastructure to fight food insecurity beyond the pandemic. While it should not take a pandemic to increase school meal access for Black and low-income students, many of these newly implemented policies have the ability to serve as long-term strategies for fighting child food insecurity. Consider the dismal rates of summer meal participation prior to the pandemic—only 14.1% of children who received free or reduced-price lunches during the 2017-2018 school year in the U.S. also received them during the following summer (Hayes et al., 2019). Thus, continuing these new policies beyond the pandemic for summer meal programs could lead to positive long-term impacts on children’s health and well-being.

Additionally, while our analysis suggests that policies and practices implemented during COVID-19 may have improved racial equity in proximity to meal access—especially during the summer, we did observe significantly lower rates of access in higher socioeconomic areas. Thus, low-income students and students of color in middle- and upper-income schools—especially in more suburban areas—may face the largest barriers in food access during the pandemic. Future policies and programs should also focus on addressing needs in these areas as well.

Finally, it is important to recognize that access does not mean equity. If students—even those in areas of increased meal accessibility—were not able to take advantage of these meal access points, then these policies need to be re-examined in light of the additional barriers faced by these students and their families. Future research should explore meal-take-up rates during the pandemic and potential barriers in accessibility.

Excerpts from this post are taken from a full working paper (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3733874)