This story was also featured on Brookings Institution’s website on April 8, 2020.

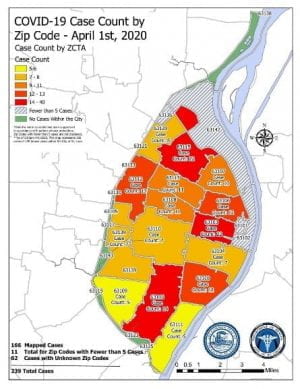

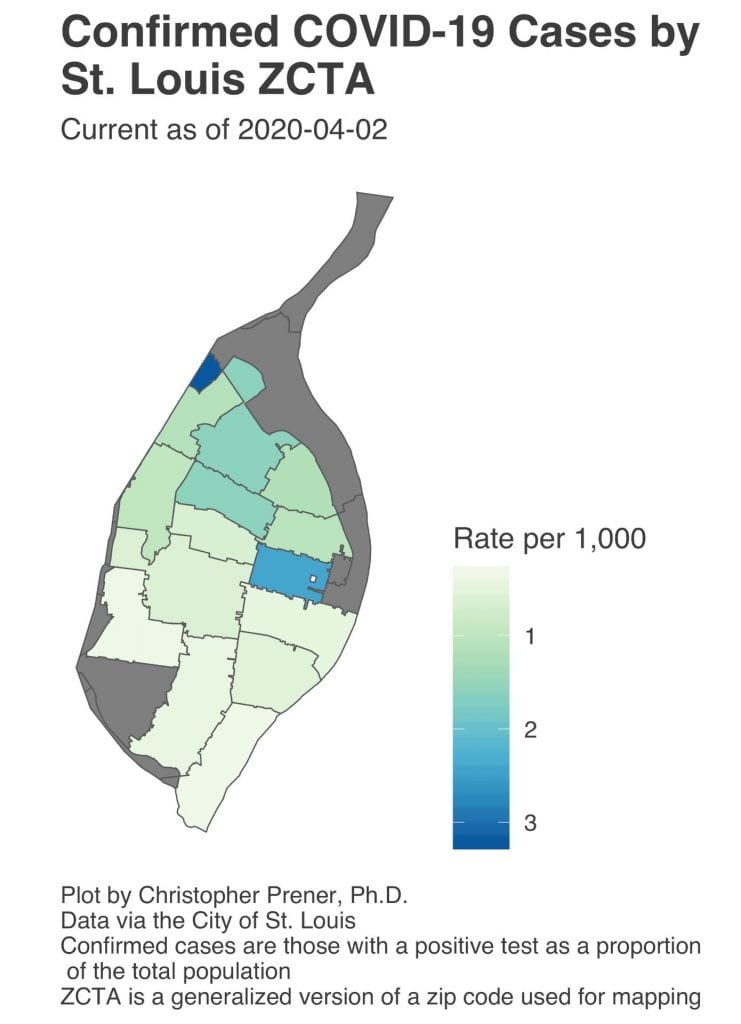

On April 1st, the City of St. Louis released the number of confirmed cases of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) by zip code. Although the number of COVID-19 tests conducted by zip code has not yet been disclosed by officials, which suggests that the data are not fully representative of all cases, we do see stark differences in COVID-19 case counts across zip codes as the pandemic unfolds across the city.

While it is clear that COVID-19 does not discriminate based on factors such as an individual’s race and economic status, we do know that it is disproportionately impacting those who are least likely to have the resources to fight it.

Overall, poverty-impacted communities are at a much higher risk of being diagnosed with COVID-19, having more detrimental health outcomes, and experiencing higher risks of death and long-lasting financial consequences. African-Americans are at greater risk because they are more likely to be low income.

COVID-19 has the potential to be particularly devastating in St. Louis. In 2018, St. Louis was ranked as having the sixth-highest rate of minority residential segregation among the 50 largest metros in the United States. Policymakers must keep the following in mind when making decisions, as poorer residents often live in under-resourced areas, are more likely to have underlying health conditions, and are unable to “socially distance” due to their financial situation or work requirements without generous employee benefits.

1. When we think about health, we often think about genetics. But in cities like St. Louis, the zip code in which you live is a main predictor for future health outcomes.

Preliminary data from the City of St. Louis shows that zip codes such as 63115 (the Penrose part of North City, bordering the Ville, Fairground and Bellefontaine) and 63103 (Midtown/Downtown west) are the zip codes with the highest number of positive COVID-19 cases (22).

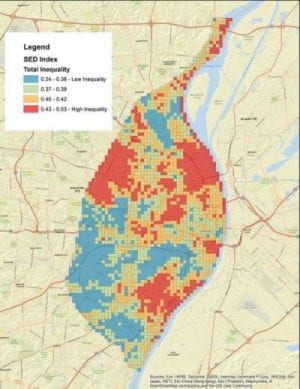

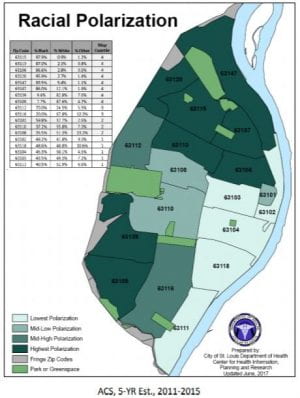

Making stronger interpretations about COVID-19’s prevalence in St. Louis will require additional data on testing, but we can compare this map with positive COVID-19 cases to others such as those showing total inequality and racial polarization in St. Louis. We see greater positive COVID-19 case counts in poorer and highly segregated zip codes in St. Louis.

Looking at the entire metro area, we can anticipate that COVID-19 will affect some neighborhoods more than others. For example, health outcomes are already much worse in The Ville (which is predominantly African American and borders an area with one of the highest positive COVID-19 case counts in St. Louis) compared to Clayton (which is predominantly white and located at the city/county border).

Babies in The Ville are six times as likely to have a low birth weight and twice as likely to die before their first birthday compared to babies in Clayton. In adulthood, people living in the Ville are much more likely to be diagnosed with asthma, obesity, and diabetes. Looking at life expectancy, people in Clayton live on average to the age of 85, but moving just a few miles down the road to the Ville, the average life expectancy drops to age 67. It is almost a 20 year age difference for neighborhoods that are only seven miles apart.

What makes the initial statistics about COVID-19 infections by zip code so alarming is that in the zip codes with the highest number of infections, people are actually less likely to get tested because of a lack of insurance or transportation, so the real number of cases might be even higher than is presently known.

The St. Louis region must work together to ensure there is adequate testing in segregated zip codes, such as The Ville, which are more likely to have a high population of residents with underlying health conditions. On April 2, Affinia Healthcare opened a COVID-19 testing site in North St. Louis City (where The Ville is located). However, there are only a total of only three testing sites in North St. Louis City which may not be enough to accommodate the total need for an already vulnerable area.

2. It is harder to socially distance if you are lower income.

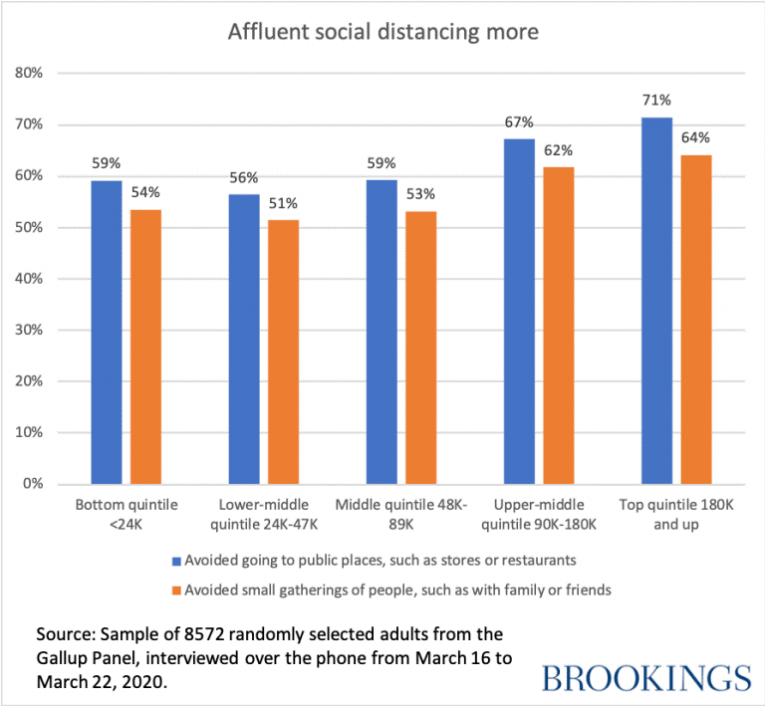

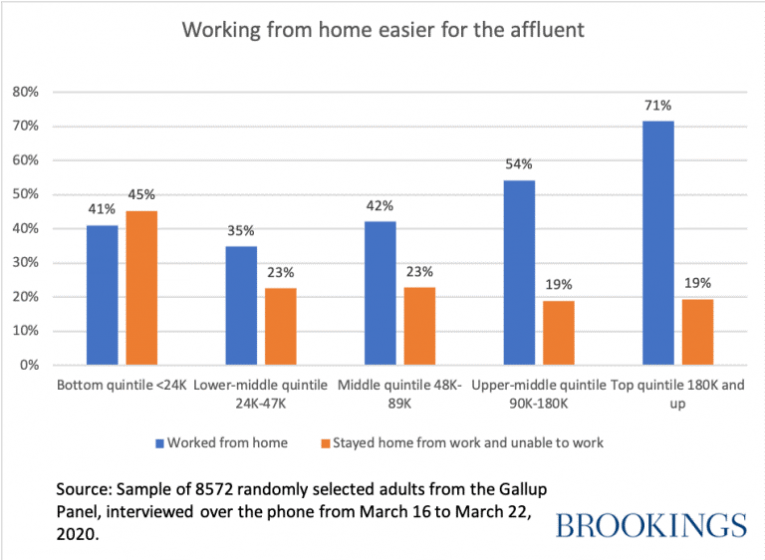

Research from the Brookings Institution has detailed how there are wide gaps by income for those who are able to work from home compared to those who are unable to do so. Being able to work from home means you can socially distance while still earning money. Yet lower-income workers have fewer opportunities to work from home, which means they may have to quit their jobs and lose what little income they have to stay at home to care for children due to school closures.

It is not just that they lose their incomes; lower-income people face risks for COVID-19 infection in daily living that higher-income people do not.

Low-income residents in St. Louis may be more likely to live in crowded areas, utilize laundromats, rely on public transportation, and are less likely to afford getting grocery deliveries to a home. Each of these realities of day-to-day life for low-income residents increases their exposure to COVID-19 infection.

3. If you are a low wage worker, you face work-related risks of infection.

For low-income individuals able to keep their jobs, going to work is risky. “Social distancing” is the main precautionary measure against contracting COVID-19 across the country, and St. Louis’ stay-at-home orders do not apply to low-wage essential workers. On one hand, it is beneficial that these workers are able to continue earning a salary. But on the other hand, policymakers in St. Louis must ensure that employees are adequately protected at the workplace.

The Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis has studied employers and frontline workers in various industries. While many of these companies are motivated to provide support to their employees, not all frontline workers receive generous employee benefits, such as health insurance coverage, vacation time, and retirement savings contributions from their employer.

Workers at “essential” businesses could be at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to those who are able to work from home. For example, certified nursing assistants at long-term care facilities are at a high risk as they work in a dense environment with very vulnerable patients. Employees at the hardware store interact with the public and cannot socially distance. Even though restaurants are now carry-out or delivery only which results in little public contact, it is difficult to stay six feet away from coworkers in a restaurant kitchen.

St. Louis, and Missouri as a whole, can look to other cities and states on positive actions to benefit low wage workers. For example, the governor of Maine is expediting a planned pay increase for low-wage health care workers by raising Medicaid reimbursement rates for providers. This reduces the burden on employers, as they operate on tight margins due to reimbursement rates. Policymakers can consider whether similar policies can be adapted for St. Louis and Missouri. In addition to receiving a single payment through proposals such as the CARE Act, attention must be given to support low-income individuals over a more sustained and longer period of time.

Disaggregated by zip code, these COVID-19 cases repeat a story we see too often in St. Louis—low-income communities of color are left with the greatest health and economic burden. Policymakers should look closely at not only this data, but the underlying social indicators exacerbating the strain on these households and communities.

We don’t need a map to tell us that policymakers, health officials, corporations, and St. Louis residents themselves must continue to break down economic barriers to create partnerships and solutions that support the most vulnerable in our city – those who were already facing a disproportionate social, financial, and health burden prior to COVID-19 entering their lives.

One Comment

Comments are closed.