As the United States nears the seventh month of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become clear that the economy will not recover simply by encouraging businesses to re-open or consumers to keep shopping. One of the key difficulties in fully restarting the economy is that many parents are facing an incredibly difficult situation in which they have to choose between their jobs and caring for children who remain at home due to a lack of child care and in-person schooling options. These parents are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and will continue to struggle without stronger federal and state support for child care.

New data from the second wave of the Social Policy Institute’s national Socioeconomic Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, administered during late August and early September, allow us to better understand the impact of the pandemic on families with children.

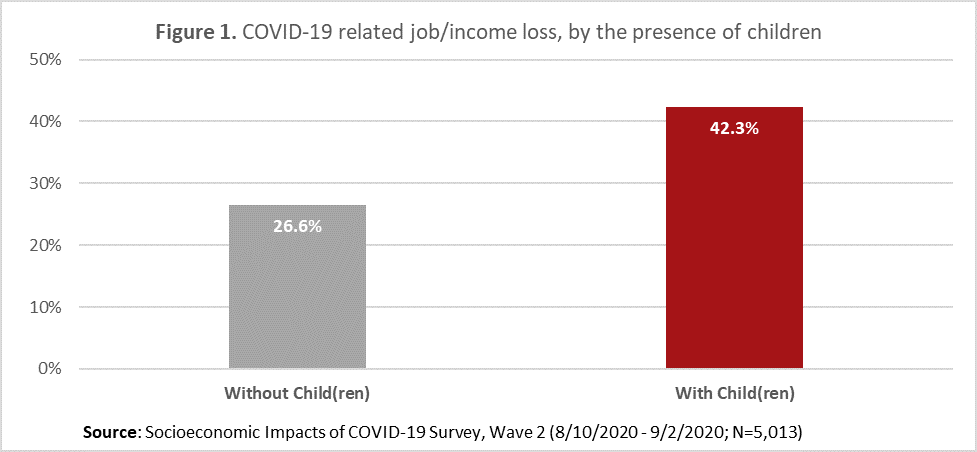

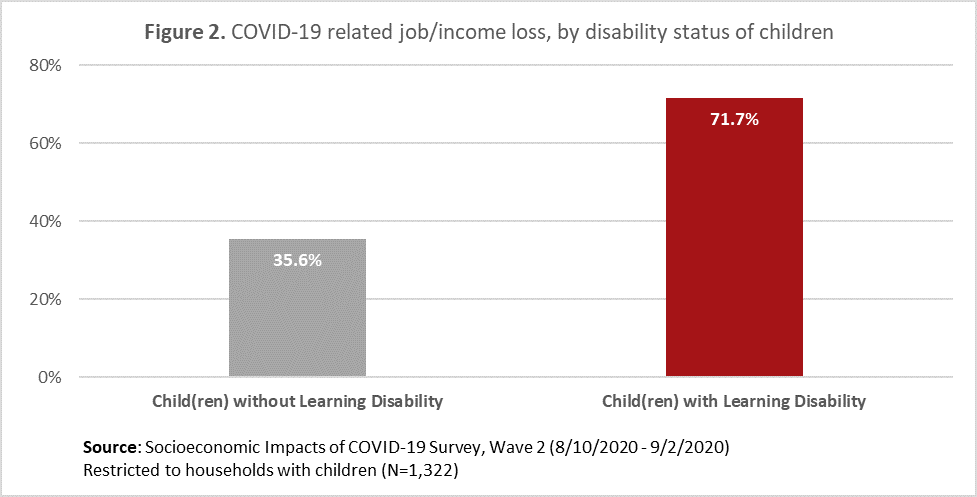

Throughout the pandemic, families with children experienced a high degree of economic volatility as a direct result of COVID-19. Figure 1 shows that, during the months of August and September, families with children were more likely to report losing a job or income due to COVID-19 (42%) as compared with families without children (27%). These job and income losses were most concentrated among parents of children with learning disabilities and parents of younger children (aged 13 or younger). For example, Figure 2 shows that twice as many (72%) parents of a child with a learning disability reported losing a job or income due to COVID, as compared to those without a child with a disability (36%).

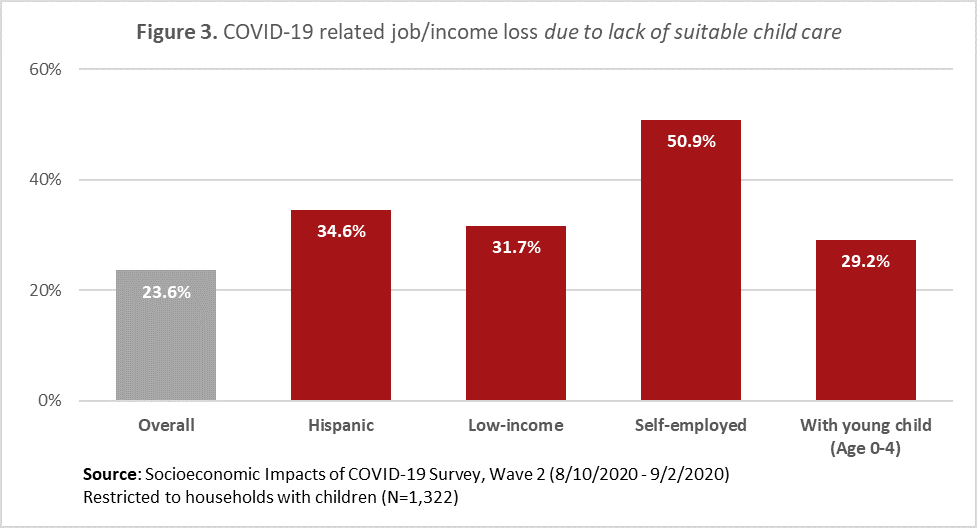

While parents of children are more exposed to COVID-19-related economic volatility, our data also show that these parents are losing jobs or income as a direct result of a lack of suitable child care as well. In total, 24% of families with children reported losing a job/income due to a lack of suitable child care, and these effects were concentrated in Hispanic households, poor households, self-employed households, and households with very young children (see Figure 3).

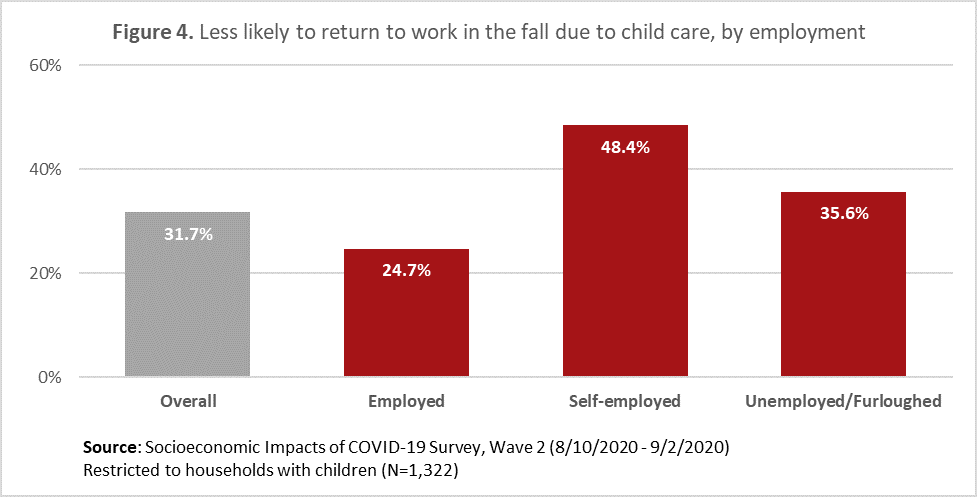

While parents of children face a disproportionate amount of economic volatility due to COVID-19, our data also show that a lack of suitable child care may be reducing work productivity and keeping parents from returning to the workforce. The survey shows that 32% of parents said a lack of suitable child care made them less likely to work in the fall, and 32% also said this lack of child care made them less productive at their jobs. These effects were strongly concentrated in self-employed households, as 48% of self-employed parents said they were less likely to return to work, roughly double the rate of traditionally employed households (25%). This indicates that a lack of suitable child care during the pandemic may be depressing both the economic recovery and entrepreneurial opportunities for parents (see Figure 4).

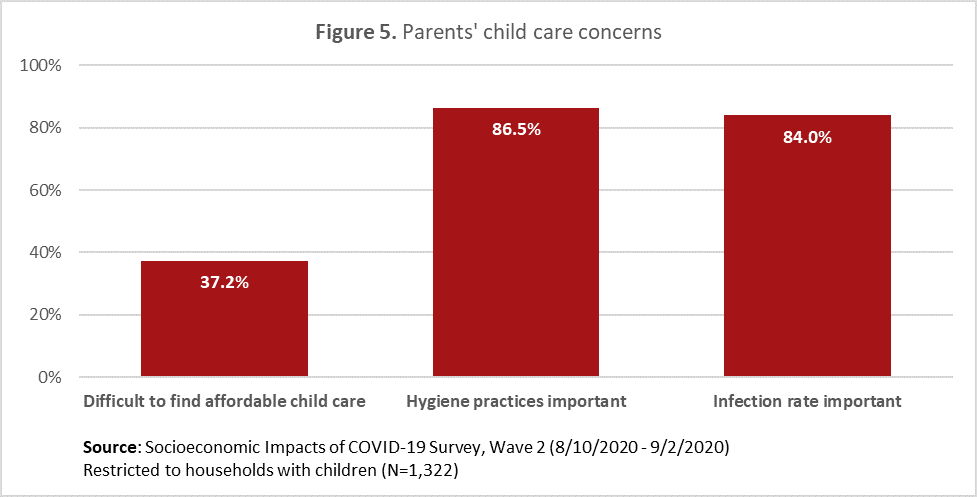

Parents have a lot to consider when it comes to child care, including cost and risk. More than one-third (37%) of parents said finding affordable child care during the pandemic was challenging. Parents are also very worried about the safety and health of the child care providers—most parents (87%) said provider hygiene practices such as small group sizes, temperature checks, and masks were important to them; 84% of parents said it was important that infection rates in their area were down before considering sending their children back to child care.

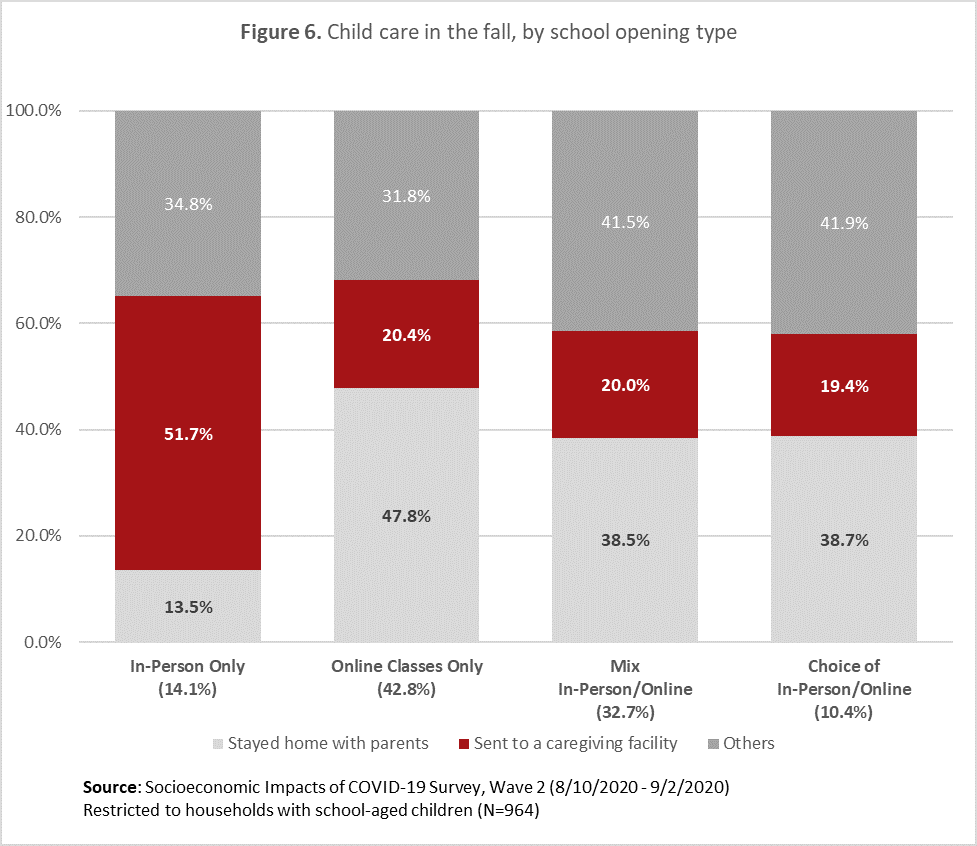

Yet despite the costs and risks, the majority of parents still plan to use some form of child care this fall; 25% plan to send their children to some type of caregiving facility (usually younger children) and 36% plan to use some other option (e.g., having the child cared for by a relative). Under “normal” circumstances, parents have some reprieve during the school year, but with only 14% of our survey respondents indicating their schools would offer exclusively in-person learning, parents have been forced to find new ways to balance work and their child’s care, and in some cases, they are making the choice to leave their job.

In Figure 6, we examine how the child care options parents plan on using in the fall are related to the type of classes schools are offering in the fall. Unsurprisingly, online education was strongly associated with keeping the child at home; however, only half of parents whose schools were offering online-only education planned to provide at-home child care, indicating that there is still a demand for child care options if children cannot attend school.

We also find that parents are getting creative with these challenges. Roughly 11% of parents in our study are planning on homeschooling their children during the pandemic, which is roughly three times higher than the pre-COVID homeschooling rate. Yet despite the efforts of these parents, the fact remains that providing parents with affordable, quality child care is integral to the country’s economic recovery. Without affordable and safe child care options, parents are often giving up their jobs, delaying their return to jobs, or working less productively in their existing jobs.

Child care facilities need federal, state, and local funding to support not only their day-to-day operations, but also to accommodate the increase in child care needs with so many parents navigating virtual learning and work. Families also need direct financial support to help them afford quality child care that they can trust to keep their children safe during the pandemic. Finally, the federal government should outline clear standards for hygiene practices and testing procedures at child care facilities in order to help families feel more comfortable sending their children for care. If policymakers are serious about promoting a quick economic recovery, they need to prioritize helping working families who shouldn’t have to make a choice between their job and their children’s health.