By: Olga Kondratjeva, data analyst III, Social Policy Institute; Michal Grinstein-Weiss, director, Social Policy Institute; Talia Schwartz-Tayri, researcher, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; John Gal, professor, The Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; senior researcher, the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel; & Stephen Roll, research assistant professor, the Social Policy Institute

The COVID-19 pandemic caused substantial social and economic turmoil on a global scale, with adverse impacts that may last for years. Israel has been grappling with the social and economic consequences of the pandemic since its onset. The number of the unemployed and furloughed employees jumped sharply in April and May, indicating a considerable degree of job loss, layoffs, and potential economic hardship during the early months of COVID-19. With the new national lockdown, we expect the number of people facing economic hardship will increase.

To study the social and economic effects of the pandemic in Israel, the Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis conducted a nationally representative online survey with approximately 2,300 Israeli respondents between June 4 and July 1, 2020. In this brief, we explore the degree to which sampled households faced job loss and layoffs and experienced material hardship during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

High rates of job loss and furlough across income groups

Our survey finds that one in four respondents across all income groups reported an employment shock—either the loss of a job or a furlough—during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

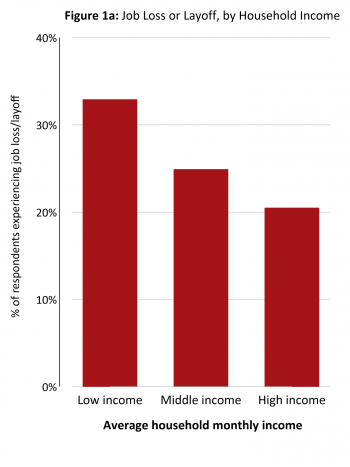

The rate of job loss and furlough, however, differed greatly by pre-COVID-19 household income (Figure 1a).[i] We find that respondents from low-income households were at a significantly higher risk of job loss or furlough: every third respondent in low-income households experienced a job loss or furlough, while one in four respondents in middle-income households and one in five individuals in high-income households lost jobs or were furloughed. These numbers are concerning, as they suggest that those who were already in a more vulnerable state before the pandemic also experienced greater employment shocks.

[i] Income groups were constructed based on self-reported household gross monthly income before COVID-19. We define low-income households as those with average household gross monthly incomes of NIS 8,000 or less (USD 2,285 or less), middle-income households as those with incomes between NIS 8,001 and NIS 17,000 (USD 2,286 and NIS 4,857), and high-income households as those with incomes of NIS 17,001 and above (USD 4,857 and above). Exchange rates correspond to June 1, 2020, and income thresholds roughly correspond to the 3rd and 6th deciles of the household gross monthly income.

Disparities in job loss and furlough by religion/ethnicity and housing status

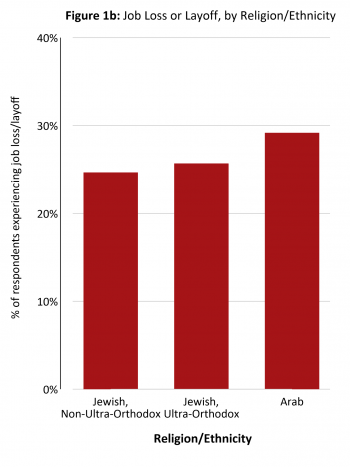

The survey also finds that relative to Jewish respondents (excluding Ultra-Orthodox Jews), Arab Israelis experienced slightly higher rates of job loss or furlough during the first three months of the pandemic (Figure 1b). While 25% of Jewish respondents (excluding Ultra-Orthodox Jews) and 26% of Ultra-Orthodox Jewish respondents in the sample experienced a job loss or layoff, the rate was higher among Arab Israelis (29%).

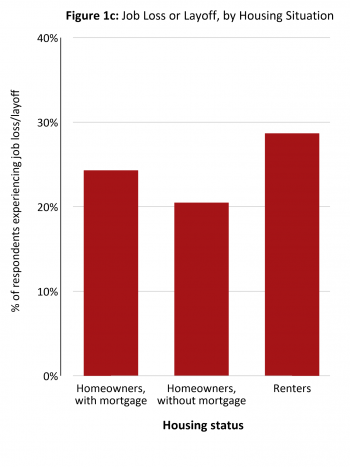

Lastly, we looked at how job loss and furlough differed according to the respondent’s housing status. We find that renters—who are likely more financially vulnerable—faced a higher risk of disruption in their employment: nearly 29% of renters experienced a job loss or furlough, compared to just over 20% of respondents who owned their homes without a mortgage (Figure 1c). This is aligned with the findings above in suggesting that the effects of the pandemic may be more negative for households who tend to face greater financial instability.

Demographics of hardship experiences

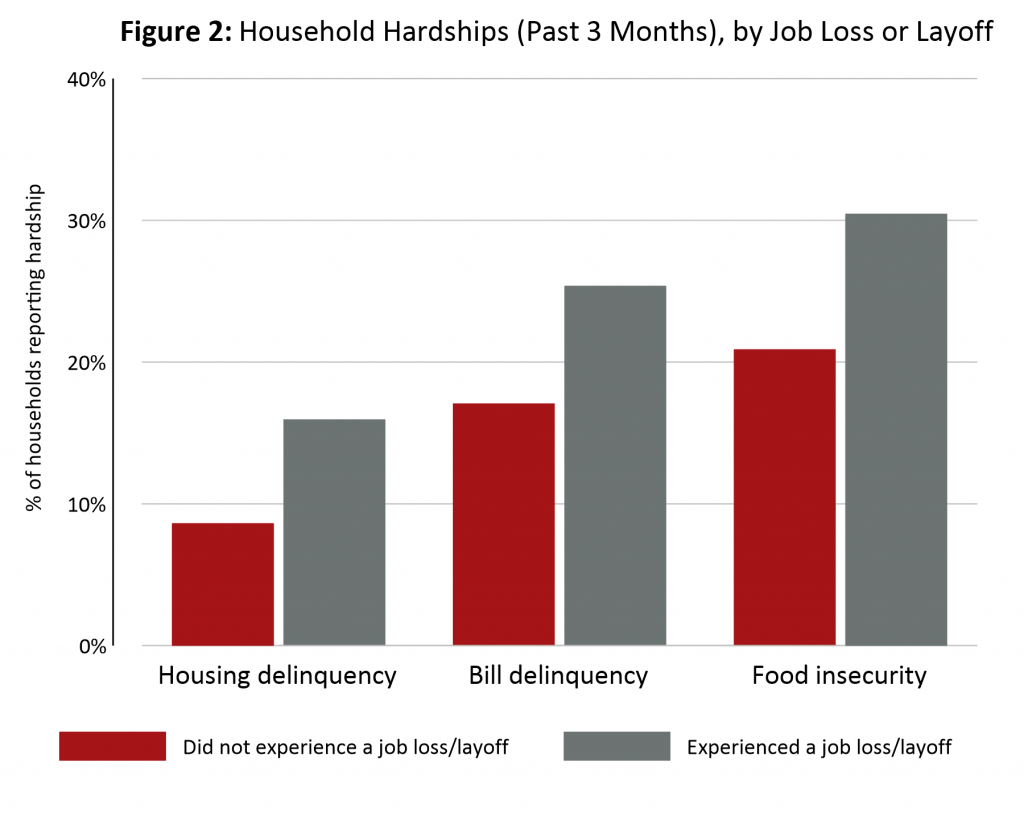

As one might expect, changes in employment situations were accompanied by high rates of material hardship during the first three months of the pandemic. Respondents who experienced negative changes in their employment status during the first three months of COVID-19 were more likely to report a greater incidence of material hardship, including difficulty in paying their mortgage or rent, paying other bills, and affording adequate type or amount of food (Figure 2). In particular, those who experienced a job loss or furlough were nearly twice as likely (16%) to report housing delinquency as those who did not experience a job loss or furlough (9%). Those who suffered a job loss or furlough were also more likely to say they experienced difficulty paying non-housing bills (25%) and food insecurity (30%) relative to those who did not lose their jobs or were furloughed (17% and 21%, respectively).

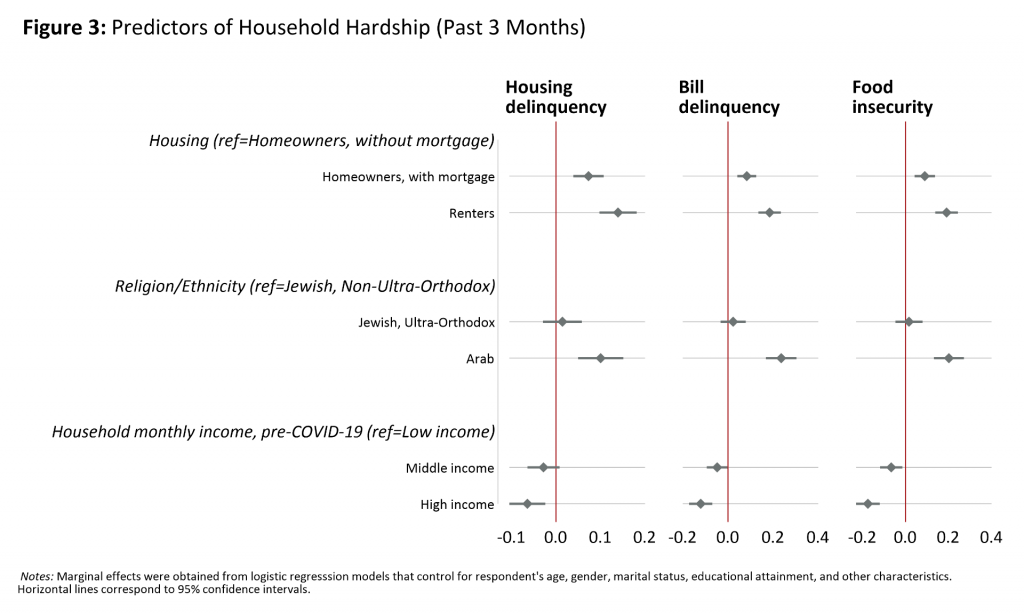

Also, findings from the multiple regression analysis indicate that the experience of hardship was strongly correlated with household income prior to COVID-19, housing situation, and religion/ethnicity, even after accounting for key demographic and financial factors including gender, age, marital status, the number of children in a household, prior employment, and the receipt of government benefits (Figure 3). That is, during the early months of the pandemic, on average,

- Households with high incomes before the pandemic experienced lower rates of hardship relative to low-income households.

- Renters, as well as families who owned their homes with mortgages, faced a greater probability of hardship relative to homeowners without a mortgage.

- While no statistically significant differences in the incidence of material hardship were detected among Jewish respondents, Arab Israelis tended to report a greater prevalence of material hardship relative to Jewish households.

These regression results mirror the findings above: as economically vulnerable households were at a higher risk of losing a job or being furloughed, they also tended to experience material hardship at a higher rate.

Exacerbating pre-existing disparities

It is not immediately clear if these differing levels of hardship across different demographic groups are driven by pre-existing disparities, if they emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, or if the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing differences. To explore this, we examined whether or not material hardship was reported as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though the rates of reported material hardship attributed to COVID-19 were statistically insignificant between the income groups, across different housing arrangements and religious/ethnic groups, statistically significant differences were observed. This applies to the reported difficulty paying bills and experiencing food insecurity as a result of COVID-19, but not the reported difficulty paying rent or mortgage. These additional analyses suggest that while the observed differences in hardships may have existed before COVID-19, the experience of material hardship may have been exacerbated as a result of the pandemic among more financially vulnerable populations (e.g., renters, Arab Israelis).

Long-term impact and implications

Our survey findings illustrate that beyond the traditional measures of unemployment and job loss, households have experienced heightened rates of material hardship during the pandemic with possible far-reaching medium- and long-term consequences. For example, prior research shows that food insecurity is negatively associated with the health outcomes of both children and adults. Similarly, households unable to make on-time payments for housing and other bills may not only be required to cover extra fees on their outstanding bills, but they may also face more serious consequences like the breach of rental agreements. This will only compound their financial crisis.

The government of Israel has implemented several measures to alleviate the consequences of the pandemic during the first months of the crisis (e.g., extended unemployment benefits, a cash grant) and more recently (e.g., an additional universal cash grant). While the effects of these policies remain to be seen, it is not unlikely that the COVID-19 pandemic may further exacerbate existing economic inequalities in Israel. Unless Israel’s government implements a more equitable response to the pandemic, the negative effects may be felt long into the future.