When you think of gig work—types of work where online apps and platforms allow workers to get paid for a range of services including ride-sharing, home repairs, art sales, and property rental—you might imagine a flexible job that enables anyone to earn income. If you have a reliable car and a smartphone, you can download an app to become an Uber driver, or you can make an Etsy account to turn your knitting hobby into a paying job. Perhaps this ease and flexibility is especially enticing in light of April’s historically high unemployment rate, but gig work is not immune to the effects of a pandemic.

Though gig employment always carried some economic risks, the recent collapse in consumer demand for many products and services combined with the uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic can create serious financial distress for people who rely on the income from gig work.

Data from a new, nationally representative survey of households in the United States, administered by the Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis, found that roughly 8% of adult respondents had earned income through an online gig economy platform between February and April of 2020. Among these gig workers, just over one in three (36%) reported working less due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

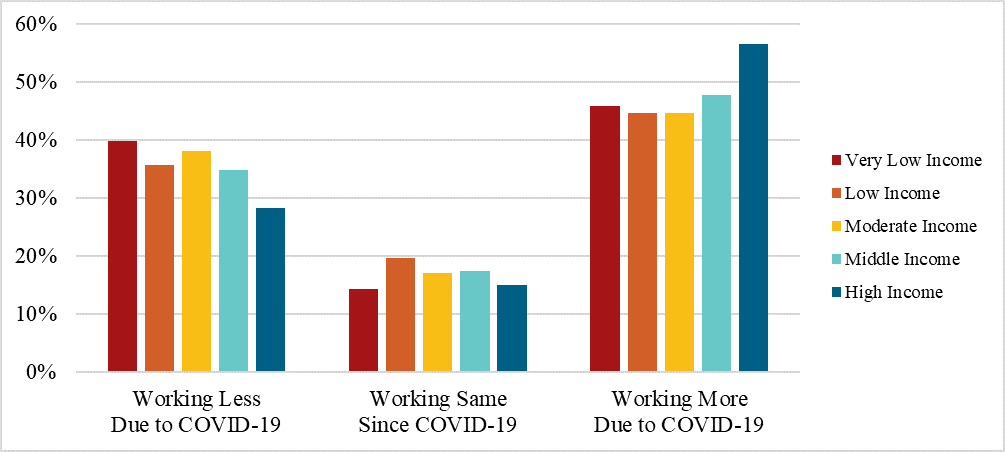

This is concerning because those who are working less disproportionately come from households that were earning less prior to the pandemic, as shown in Figure 1. Simply put, households that earned more before the pandemic are now doing more gig work during the pandemic, while households that earned less before the pandemic are working less.

Figure 1: Change in Gig Work after COVID-19, by Income Level (N = 329)[1]

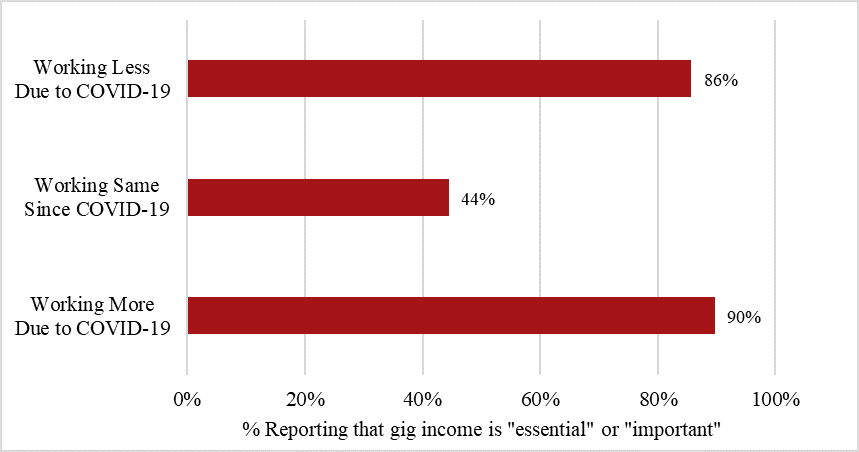

The vast majority of gig workers (81%) we surveyed said that the income they earned through the gig economy was either essential for meeting basic household needs or was an important component of the household’s budget. As Figure 2 shows, over four-fifths (86%) of those working less during the pandemic said that their gig income was either essential or important for their household budget. This suggests that workers who have been forced to reduce the amount they work in the gig economy—a group of people who already had disproportionately low incomes before the pandemic—may be in a uniquely vulnerable financial position.

Figure 2: Rate of Reporting Gig Income as “Essential” or “Important” by Change in Work Due to COVID-19 (N = 329)

Although the results presented here represent just the first cross-section in what will be a longitudinal study, it seems clear that COVID-19 is impacting the financial lives of gig workers. Lower-income gig workers are working less due to COVID-19, and a strong majority of those individuals depend on this income as an important component of their household’s finances.

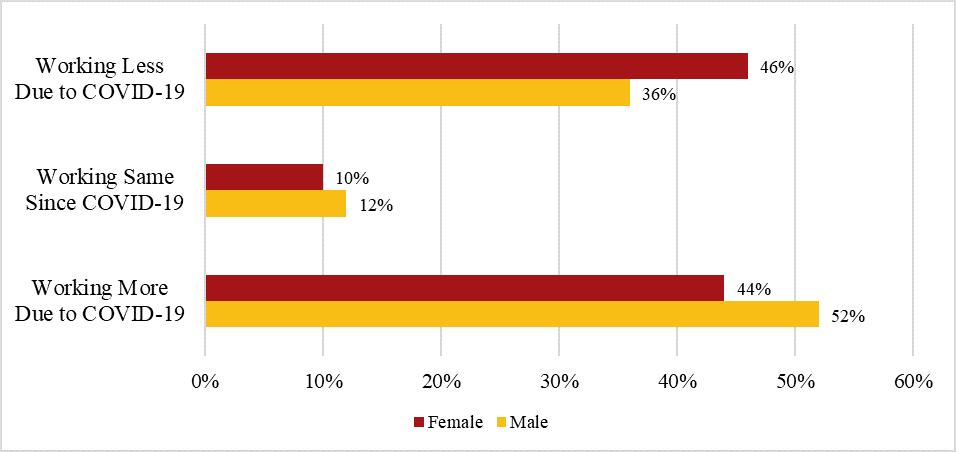

More investigation is needed to understand what is driving these changes. For example, in our data, we see some evidence suggesting that demand for relatively low-paying gig work has largely declined. We also see some evidence suggesting that family dynamics and gender may play a role in who works more or less during COVID-19. For example, among gig workers with children, men were nearly 20% more likely to report working more while women were about 30% more likely to report working less (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Change in Amount of Gig Work by Sex, Restricted to Gig Workers with Children (N = 199)

SPI will continue to accumulate data around the impact of COVID-19 on gig work, but findings suggest that the most financially vulnerable gig workers are those who are losing the most work. While the U.S. Department of Labor did extend eligibility to gig workers for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance under the CARES ACT, additional support may be necessary. For example, policymakers should consider additional cash transfers like the recent economic impact payments, ensure continued support for the existing array of social support programs (such as SNAP and expanded unemployment benefits), and child care subsidies. These small but necessary steps could help balance the impact of the vulnerable gig industry.

[1] “Very Low Income” refers to workers whose 2019 household income is less than 50% the Area Median Income (AMI). “Low Income” refers to workers whose 2019 household income is at least 50% AMI and is less than 80% AMI. “Moderate Income” refers to workers whose 2019 household income is at least 80% AMI and is less than 120% AMI. “Middle Income” refers to workers whose 2019 household income is at least 120% AMI and is less than 170% AMI. “High Income” refers to workers whose 2019 household income is at least 170% AMI.