From discussions of universal basic income in the 2020 presidential debates to repeated stimulus checks during the COVID-19 pandemic, government cash transfers have received a lot of attention recently. When considering a cash transfer program, policymakers usually have an objective in mind, such as reducing economic inequality, improving households’ ability to meet basic needs, or stimulating the economy through increased spending. In order to know whether a cash transfer will help further a desired goal, it is important to know how recipients are likely to use the money. Recent Social Policy Institute research suggests that how people will use a cash transfer likely depends on both the amount of the transfer and the frequency of the transfer (e.g., as a larger one-time payment or as a smaller monthly payment).

As part of our Socioeconomic Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, we asked a sample of 4,887 adults how they anticipated they would use a direct cash transfer. We used quota sampling to make sure our sample approximately reflects the characteristics of the U.S. population in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and income. We randomly assigned survey participants to one of four groups. Each group received a slightly different version of the same question:

“If you received a [frequency] payment from the federal government of [amount] from the federal government with no strings attached and no matter your financial situation, how would you use this money? Select all that apply.”

Table 1. Experimental group by frequency of a cash payment and amount of each payment

| Group | Frequency | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Monthly | $250 |

| Group 2 | Monthly | $500 |

| Group 3 | Lump sum | $3000 |

| Group 4 | Lump sum | $6000 |

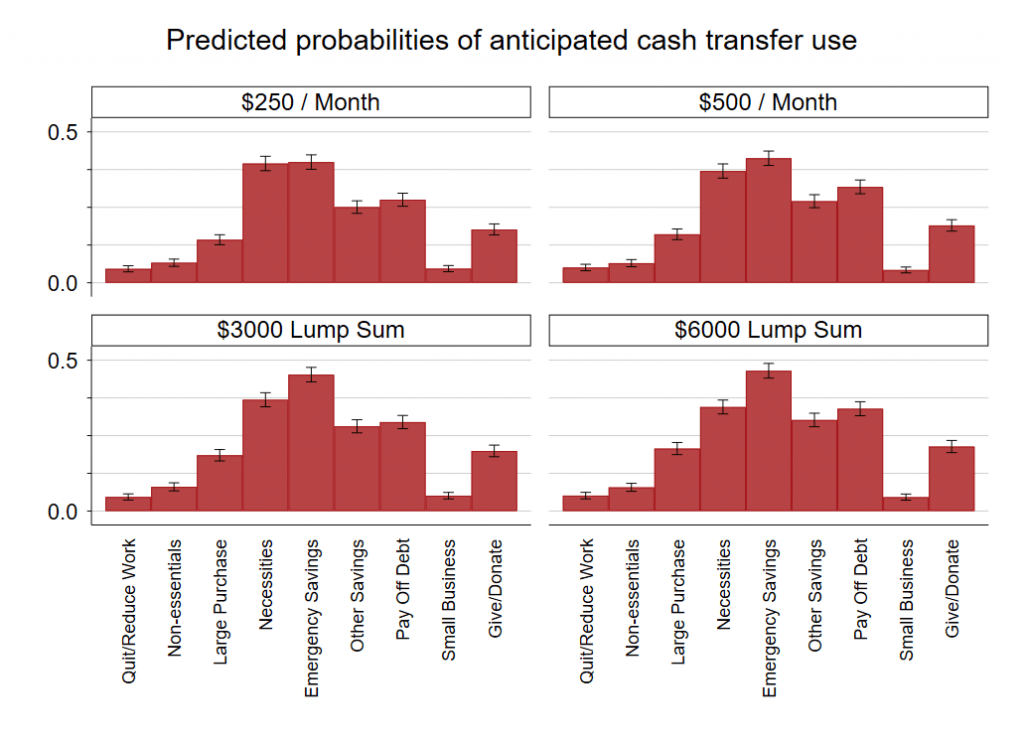

Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of each anticipated use of money for each of the four treatment conditions. There are many similarities across groups. Very few people in any group said that they would quit work or reduce their work hours. The most common uses for every group were paying for necessities and saving for emergencies. Few people said they would spend the money on luxuries or non-necessities. While these survey responses may be due in part to social desirability bias, a universal basic income pilot program in Stockton, California which distributed $500/month to 125 individuals showed similar results: recipients were much more likely to spend the money on necessities than luxuries.

Our results also find that the frequency and amount of cash transfer changed how individuals said they would use the money. We examined differences in projected use based on (1) frequency of payment and (2) smaller vs. larger payment amount. Those who were asked about receiving a lump sum payment were more likely than those asked about a monthly payment to report that they would use the money to save for an emergency, save for other purposes, make a large purchase, or give to charity or family members in need. For each of these uses, the amount did not make a significant difference. In contrast, being asked about a higher amount increased a person’s likelihood of reporting that they would use the money to pay down debt. There were no significant differences between the groups for using the money to quit or reduce work hours, start or expand a small business, pay for necessities or spend on luxuries or non-essentials.

These results are potentially useful for guiding the way cash transfers are distributed. This experiment suggests that the frequency of a payment may not significantly affect whether an individual uses that payment to make more routine purchases, such as food or small luxuries. However, individuals who receive larger lump sum payments may be somewhat more likely to spend the money on larger purchases, such as a vehicle, an appliance, or a home improvement. Thus, lump-sum payments may be more useful for stimulating spending in these sectors. Likewise, lump-sum payments may be more effective at encouraging emergency savings. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic began, only 6 in 10 Americans reported that they would meet a $400 unexpected expense with cash or a cash equivalent. As pandemic-related financial shocks have further depleted many households’ savings, rebuilding emergency funds must be a priority in order to establish financial stability in American households.