Evictions appear inevitable. Policymakers from the CDC to state legislatures are trying to stem the flow of evictions, but they still keep coming due to “gaping loopholes” in federal, state, and local moratoria. And those moratoria, even if patched, won’t solve the issue of past-due rent. Renters need financial relief, but the question is, which renters need the relief most and how do we get it to them?

We already know the basic demographics of who is most likely to be evicted. Past research establishes that Black and Latina female renters are at greater risk for eviction than white renters, a trend that has persisted into the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, households with children are more likely to be evicted.

However, these insights don’t tell us enough about how to target anti-eviction aid. As congress considers expansions of housing assistance funding, we need a strategy to get that money to the renters most in need of financial support, and we need to do it in the least cumbersome and fastest ways possible. Rental assistance funding approved in December has lagged in reaching renters in need, with only five states actively distributing funds as of February 16, 2021.

One immediate approach to get money to those who need it the most: send rental relief straight to Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) recipients.

New evidence from the Social Policy Institute’s multi-wave Socioeconomic Impacts of COVID-19 Survey shows that during the pandemic, TANF recipients were evicted at significantly higher rates than non-recipients, even when accounting for differences in demographics, income, assets, recent job loss, and how many months behind they are in rental payments.

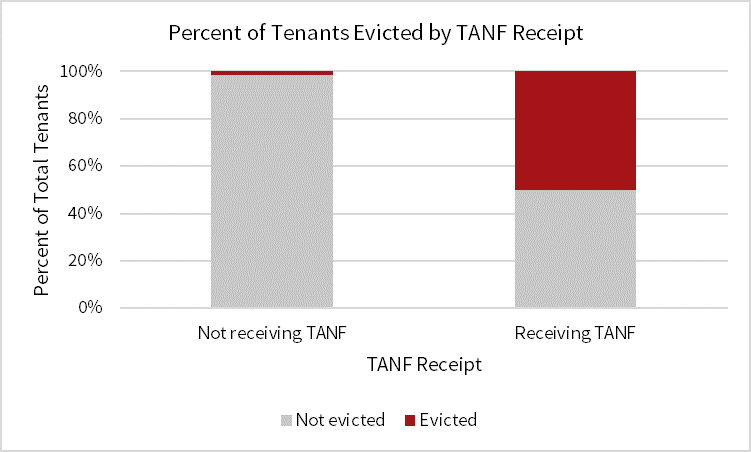

Figure 1. Evictions by TANF Receipt

N=2,963

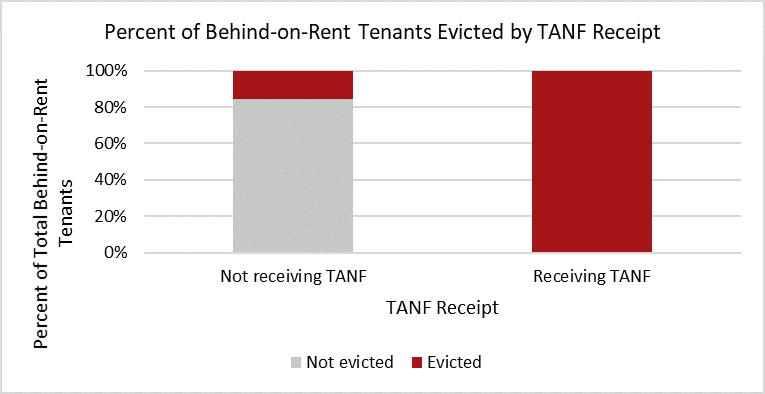

In our sample of renters, half of those receiving TANF were evicted as compared to only 1.5% of renters not receiving TANF (Figure 1). When we took a closer look at tenants who had fallen behind on their rent, the picture became even starker. Every single TANF recipient who was behind on rent was evicted as compared to only 18% of non-TANF recipients (Figure 2). Put another way, four out of every five non-TANF receiving renters who fell behind on payments were able to avoid eviction while not a single recipient of TANF in our sample had the same protection.

Put another way, four out of every five non-TANF receiving renters who fell behind on payments were able to avoid eviction while not a single recipient of TANF in our sample had the same protection.

Figure 2. Evictions for Behind-on-Rent Tenants by TANF Receipt

N=150

The amount a tenant was behind on rent didn’t matter either. Even TANF-receiving tenants who made partial payments (less than a month of rent) were evicted. This finding shows the need for immediate rental relief without a laborious process of demonstrating need. Many current rental relief programs require tenants to provide evidence that they are behind on their rent to receive aid, and these findings show the risk of that process. By the time tenants prove to the aid-administering program that they are behind on rent, it could easily be too late for them to avoid eviction.

Luckily for policymakers, guidance on how to use TANF to distribute rental relief has already been generated. As Justin Schweitzer writes for the Center for American Progress, states can act immediately to boost direct cash payments for TANF recipients. In 2019, the average monthly TANF payment was $447, an amount equivalent to about half the average monthly rent of $883 for TANF recipients in our sample.

Without additional administrative burden, states can increase TANF payments right away to all households already receiving aid to help cover this gap and avoid mass evictions. Knowing that TANF recipients are at disproportionate risk for eviction, we can be confident that this aid will automatically target and support households most in need.

All differences in eviction by TANF receipt were significant at p<0.001.

Further analysis of the disproportionate evictions of TANF recipients is forthcoming in a Social Policy Institute working paper.

Notes about eviction measurement:

To measure eviction, the survey posed the following questions:

- In the last three months, was anyone in your household forced to move by a landlord or bank when you did not want to?

- [If yes]: Why was your household forced to move?

- An eviction by a landlord

- Foreclosure by a bank or mortgage holder

- Some other reason (please specify)

Our outcome variable is dichotomous, divided into renters who did not say they experienced an eviction by a landlord and renters who said they did. We did not pose questions about the court proceedings of the eviction, so respondents who answered that they experienced “an eviction by a landlord” may or may not have had an eviction case brought against them and received a ruling for eviction. After an examination of responses for the “some other reason” option under the “why was your household forced to move” question, we did not include these individuals in our final group of those who were evicted. Many of the responses did not provide clear information about the nature of the move and others noted that they were forced to move by a university or by a roommate rather than a landlord.