Medicaid Buy-In (MBI) has received public and policymaker attention in recent years as an option for states to expand access to healthcare.

“Eligibility can be so confusing and complicated it presents an obstacle for providers and government alike to communicate clearly, never mind promote Medicaid buy-in for working people with disabilities.”

Kimberly Lackey, Director of Public Policy and Advocacy, Paraquad

Historically, MBI programs emerged as state-administered programs meant to provide support for working individuals with disabilities and to remove possible barriers from working. Over time a benefit cliff emerged where the cost of private or commercial insurance would require individuals with disabilities to choose between work or health care coverage of services that support daily living. MBI is currently offered in 45 of the 50 states, but programs can have several barriers that may hinder people from participating.

A recent study done by the Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis reviewed previous research published on Medicaid Buy-In programs and completed a scan across all states with programs in operation. Highlighted in a recent working paper, All Over the Map, factors such as access to information, limits on income and assets, and variability between states have implications for MBI program participation.

The first hurdle faced by someone interested in participating in an MBI program is access to information about the program. The publicly available information about MBI programs is often inconsistent and difficult to find. Out of the 45 states that offer these programs, 40 of them have the information on the state websites, with the other five paying non-profit organizations to administrate the information to the public. The lack of access to information about the benefits of the program greatly decreases the number of applicants.

For applicants who find information about MBI programs, it is often confusing and inconsistent enough to deter applicants from enrolling. Notably, different attempts to catalog program elements (Musumeci et al., 2014; Hall, 2015 ) around similar times have found different information about program criteria. When evaluated only 23 state policy searches agreed on four unique policy scans. Researchers did not find any evidence of a clear pattern or cause for the differences in the other 22 state policy searches. States can encourage participation by equipping potential benefactors with clear and congruous information. Effectively communicating this information not only bolsters program confidence among benefactors but also providers and policymakers.

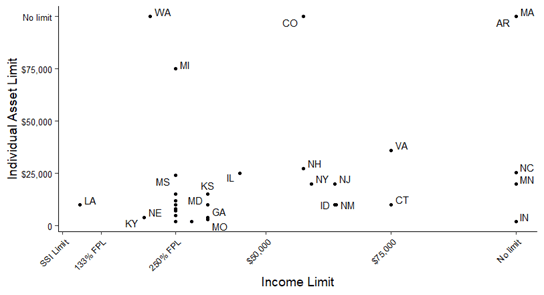

Researchers also found that eligibility criteria vary significantly between states, with factors like income and asset limitations determining eligibility. Figure 1 below shows the variability of the eligibility criteria between states based on income and individual asset limits. The limits for annual income range from $12,670 to $75,000, with five states having no limit, and some having an income limit set at 250% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) threshold. Individual asset limits also vary widely between states, ranging from as low as $2,000 up to $75,000. Four states have no limits for individual assets.

Figure 1. Variability of the eligibility criteria between states based on income and individual asset limits

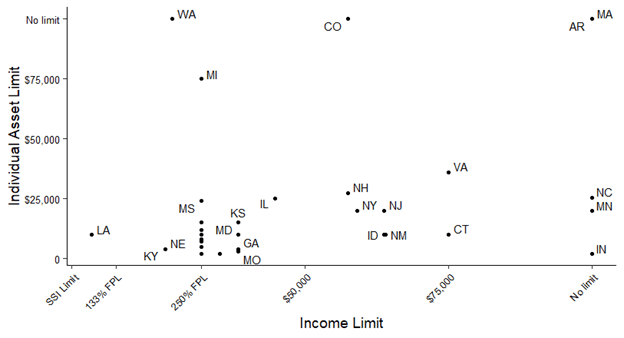

Additional features offered by MBI programs also vary between states. Different states offer up different lengths of time as a ‘grace period’- the length of time a person can stay enrolled in an MBI program without working for wages. Some states do not offer a grace period at all. Some states offer “until the next month”, while other states offer two years as a grace period. Grace periods are a critical piece of ensuring workers’ rights and protecting individuals during unplanned work interruptions states also differ in the individual asset limitations that they set. Some states count vehicles as assets while others do not. Figure 2 shows state income and asset limits for MBI program eligibility. The limits for individual assets range from $2,000 to $75,000. The limits for couple or family assets range from $3,000 to $40,855.

Figure 2. State income and asset limits for MBI program eligibility

While some states have taken steps to make their programs more accessible, the majority still have program components that limit earnings and asset increases for individuals covered by Medicaid for critical services. State-administered MBI programs aim to encourage asset and income growth for people with disabilities while providing continued support for critical healthcare coverage that is inaccessible to many via the private and commercial market. The goal of MBI programs is to support working individuals with disabilities to successfully pursue employment and grow their income assets without risking the loss of critical health insurance coverage. Research suggests positive benefits resulting from MBI programs in terms of employment and earnings. By increasing access consistently, states can foster positive outcomes for working individuals with disabilities.

As the COVID-19 pandemic passes the one-year mark, many Americans continue to deal with the uncertainty of job security and unemployment even with the adoption of corresponding COVID-19 policies. For many individuals living with disabilities, the impacts and uncertainty can be even more burdensome. A recent review of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Jobs Report highlights decreased labor force participation rate for working-age people with disabilities.

It will be critical to further develop research surrounding Medicaid Buy-In in relationship to broader efforts to expand access to insurance as states continue to grapple with the outcomes of this pandemic. Improving such research will inform policymakers and providers in individual states to develop a better understanding of program components that encourage participation. MBI programs in turn could continue and grow in improving the overall health and well-being as well as financial security of working people with disabilities.

Information for this article was taken from a current working paper supported by the Centene Center for Health Transformation and the Centene National Disability Advisory Council. Read the full paper here: (https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/spi_research/41)